|

|

|

|

The appalling reality of Bosnia’s missing dead

Thousands of families are still waiting for

news of missing loved ones, 25 years after the bloody Balkans war.

Ed Vulliamy meets the scientists piecing together the evidence from

mass graves, and the relatives hoping for justice – and a body to

bury.

By Ed Vulliamy

12 December 2016

|

|

|

|

Warning: Contains descriptions which

some readers may find upsetting

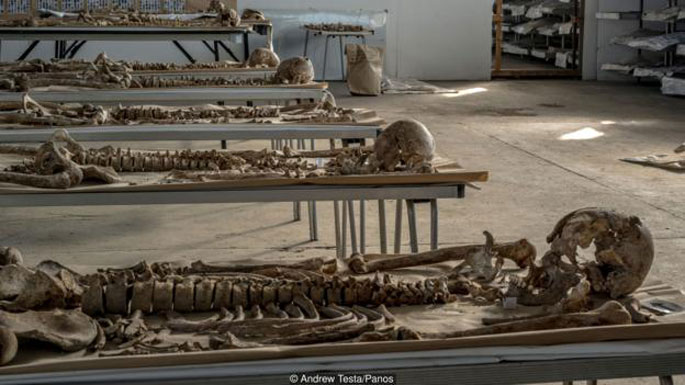

They are the unquiet dead. Laid out in

rows across the interior space of a former industrial building on

the edge of the Bosnian town of Sanski Most, the remains of human

beings, in various degrees of integration. Some of the skeletons are

almost complete, others just a pelvic bone and some assorted ribs,

arranged as though to await the arrival of more, towards the whole.

The eye sockets of their skulls seem almost to tell the violent

story of execution with a terrible silence; all sound in this space

is dulled, muted, by a pale light cast through high windows. There’s

a single bullet hole through the crown of each one.

This place was used to process wood

before Bosnia’s war of the early 1990s, and now it processes – it

endeavours to assemble – the dead. The remains are laid out on

raised trays, and at the foot of each lie possessions and clothing

found with the body when it was exhumed, invariably from a mass

grave. So to walk through this hall of death is also to walk through

these people’s lives and last moments. A pair of trainers here, a

checked shirt there, a watch or wallet. What made this person choose

a yellow sweater rather than another on a market rail, and chance to

be wearing it when taken out to be murdered? Why striped socks

beneath this half-assembly of bones, plain ones to accompany the

next? Who were these people? That is the question.

Because in addition to the spectral

presence in this building, run by the Krajina Identification

Project, there is diligent purpose. These dead people had been

missing for 24 years, along with tens of thousands of others, while

their families – survivors of the hurricane of violence that blew

through this corner of Europe in 1992 – searched, wondered, feared

the worst. Now they have been found – but who are they?

This facility is one in a chain that

seeks to answer that question, the work of which is the most

remarkable entwinement of science, human rights and justice in the

world today. The task of that chain is to locate and exhume the

40,000 people who went missing after the western Balkan wars – the

worst carnage to blight Europe since the Third Reich – then to

assemble their remains insofar as they can be found, identify them,

give them names, and return these dead back to the living for

burial. It is scientific work at its most committed and advanced,

helping to meet humankind’s most primal need: to bury or in some way

ritualise the remains of our dead.

|

|

|

The belongings of the dead are

laid at the foot of each table holding a skeleton at

the Krajina Identification

Project in Sanski Most (Credit: Andrew Testa/Panos)

|

|

|

Beside a rough road that climbs a remote

mountainside, between the towns of Prijedor and Sanski Most, lies

the house that Zijad Bacic has rebuilt in the hamlet of Carakovo,

from the ashes to which it was charred in 1992, and where he now

plays football with his son, Adin. Beside it a modest marble

monument has been raised, on which are carved the names of 38

people, many of them members of Zijad’s extended family. Some of

them were killed on the night of 25 July 1992; others vanished.

Zijad was 15 on the night that – after his father and most other men

had been taken away to concentration camps – Serbian death squads

came back to “mop up” the women and children. He recalls it vividly:

“We were at home when we heard the soldiers’

voices. ‘Come on out! Come on out!’ My mother gestured to us: we

must. As soon as they went out, and the other families around us,

machine guns began firing. I recognised one of the men, the others

wore balaclavas. They were about five years older than me. I watched

my mother hit first and fall down, then my brother and sister – and

I ran behind a bush to hide. I stayed there until they had finished

shooting and shouting – I recognised another of the balaclava men

from his voice; they came from just down in the valley, they were

neighbours. I saw their arms shooting pistols at those who were

still living, until they stopped screaming.

“The killers went, and slowly I emerged. I saw two

other children, a boy of 10, a girl of 13. We looked at each other

as though we were ghosts. We were the only ones of 32 in the hamlet

to survive. I saw a man sitting on that bench there – he looked as

though he was asleep, but he was shot dead. I saw my mother – Sida,

she was born in 1946 – and my brother Sabahudin and sister Zikreta

dead in the garden.

“But I survived. I can still hear their voices,

the shooting. I was deported on the convoys, and went to a refugee

camp in Germany. And I never thought I’d come back here, but I

couldn’t sleep without knowing… what happened? Where were they? I

had to find my missing father, all my uncles, and to find where they

had buried my mother, younger brother and sister.”

|

|

|

Fikret Bacic at his home in

Carakovo, near Sanski Most. 29 members of his

extended family were taken by Bosnian Serb forces

and killed in July 1992 (Credit: Andrew Testa/Panos)

|

|

|

It is mid-afternoon, the rain of morning banished

by a breeze from the west, and sunlight strokes the beauty of the

hillside. Blue and yellow summer flowers are scattered across the

meadows. Adin swings his scooter around. “I reported everything I

knew. I gave blood [to help investigators find DNA matches], and

started digging where I thought they might be,” says Zijad. “A

Serbian lady came: ‘Why are you digging here?’ I said I’m looking

for my family. She said: ‘They’re not here. Try somewhere else.’ I

believe that 99% of the people here know exactly where they are.

Only they don’t care to tell me, or they’re too afraid of the people

who did it. But I need to know where. I need funerals. I need

trials.”

There have been seven arrests in connection with

the extermination of the Carakovo villagers. Two of the accused have

been released on bail under house arrest, and Zijad thinks they are

the men he recognised on the night of the massacre. “That’s one of

their houses right there,” he says, pointing towards a white

building on the valley floor. “We’re hoping that these trials will

reveal where my family is. I’m going to testify. Even though we’re

surrounded by them, I have no fear of anyone or anything any more.

All I have is my wife and son, and my only need in life – which is

to find those I have lost.”

Where Zijad’s mountain lane meets a tarmac byway,

there stands a little shop kept by Zijad’s uncle, Fikret Bacic, who

takes my notebook and writes a list of the names of his extended

family who went missing during the last week of July 1992. It takes

him a long time; there are 29 of them, including his mother Sehrisa,

his wife Ninka, son Nermin, who was 12, daughter Nermina, who was

six, four brothers including Zijad’s father, three sisters, several

aunts, uncles and cousins. Of the 29, 19 are children; the youngest

was two.

Fikret’s eyes are the saddest imaginable, as

unfathomable as his loss is inconsolable. “They were taken and

killed by the viaduct, just there, by the main road,” he points to a

railway bridge beneath which we’d just driven. “For years, I’ve had

no idea where they were buried.

“I was working in Germany when it happened; of

course I couldn’t believe it.” The first thing Fikret did was to

tour refugee camps across Europe: Holland, France, Austria, Croatia.

“I hardly knew what I was doing, like a wild hunter-dog. But

nothing. So there was only one thing to do: come back, and I never

thought I’d do that, back to the destroyed house. But I did, in

1998, only to start looking, for I had nothing else to do with my

life but find the bodies and the people who did this. I asked a

Serb, who had been the best man at my wedding, raised by my

grandmother: where are they? There are not many people I can ask, I

pleaded with him, I just need to know who did this, and where they

are buried. He just said: ‘I don’t know, I was not there.’ I could

tell he was lying. I went to the police in Prijedor, but everyone

knew it had been the police who organised the hiding of the bodies.

Two men knew – I had a feeling. I went to the house of one, but he

had guests and would not talk. Then the other, but he had died. Then

I realised the only thing to do was to start digging.

“I dug everywhere. I helped wherever there was a

dig.” Fikret went to the mass grave found at the village of Kevljani

in 1999, next to a concentration camp established by the Bosnian

Serbs at Omarska; it had been found when villagers spotted strange

vegetation growing, of a kind the soil beneath it would not normally

nurture. There was no sign of Fikret’s family.

Then, in 2004, work began at a second mass grave,

also near Omarska, at Tomasica. Fikret was there, digging, but the

bodies found there still did not include his family. “None of us

knew,” he says, that “we were only 100 metres from the biggest mass

grave of them all”.

We sit in Fikret’s yard, beside the shop, roses

climbing the fence, neighbours passing by, saluting him. He sips a

glass of Nektar beer, a Bosnian Serb brew. “The pain doesn’t go

away, it gets worse, stronger, the longer it lasts,” he says. “I

went to the state court, and an American prosecutor showed an

interest for a while, but then said he had to leave and take another

job. After a while, I gave up, I couldn’t go on any more.” Then, in

2013, there was a bigger, macabre discovery at Tomasica: hundreds

more bodies, buried, hidden – but now revealed. Fikret Bacic was

there moments after the first earth was broken and news sent abroad.

“Whenever I could go, I was there. It seemed that

they had buried them village by village, in order of where they’d

been killed along the road from Prijedor. Go deeper, go deeper, we

all said. We had all given blood by now, and first, they started to

find my neighbours, the Tatarevic brothers, up the lane there. Then

a cousin of mine. And then my brother Refik – no documents, but the

DNA matched.

“It’s hard to say what I felt. It was like someone

who belongs to me coming back from 10 metres deep. He’s my family.

And then another body comes out, and it’s not one of mine, and you

feel so bad. I did that for three months, until the last body was

found and either identified or not. Now we must wait for another

grave to contain the women and children: two were found at Tomasica,

but still 17 kids are missing, aged two to 16. You know, I can’t

believe I’m saying this; it leaves a bad taste in my mouth, and in

this lovely evening, for me to have to tell you that all this is

true, that this is what people do to each other.”

|

|

|

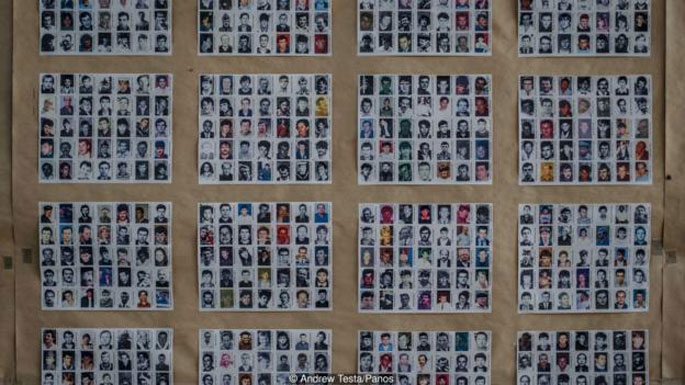

Photographs of the missing at the

Krajina Identification Project in Sanski Most

(Credit: Andrew Testa/Panos)

|

|

|

The driving force behind this search for the

missing dead in the blood-drenched Balkans is the International

Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP), founded in 1996 on the basis

of an initiative by President Bill Clinton at a G7 summit in Lyon,

France. ICMP arrived to urge the location and identification of

30,000 people in Bosnia (and 10,000 more across the region),

‘missing’ in mass graves. Over two decades, this it has done, both

physically and scientifically, spearheading a battle against what

appeared to be all odds. Most have been found and their remains

returned to their families – but 8,000 in Bosnia are still missing.

The scope of what ICMP has been doing here in

Bosnia since its foundation is almost beyond comprehension.

Originally a non-governmental organisation, it was recently given

full international legal status, covered by treaty. So now, from

these benches holding their skeletons in Bosnia’s rural reaches,

ICMP takes on the world. This work addresses the existentially

offensive limbo suffered by tens of millions of families around the

planet – the state of not knowing, not having so much as the remains

of a child, husband, wife or parent, to do what humans have always

done: bury them.

Gruesome battle

Over the summer of 1991, the break-up of

Yugoslavia began to turn bloody, first in Slovenia, then Croatia,

then Bosnia, as Yugoslav republics sought independence and Slobodan

Milosevic’s government inBelgrade sought to establish borders for a

“Greater Serbia”, which spread into both Croatia and Bosnia and

entailed the elimination, through death or deportation, of every

non-Serb on the territory.

In Bosnia, a savage pogrom was unleashed in spring

1992, mainly at first against Slavic Muslims in the east and against

Bosniak Muslims and Catholic Croats in the north-west Krajina; the

Bosnian capital of Sarajevo was subjected to relentless siege and

the stillborn republic torn apart.

It was my accursed honour to report on this war,

and in August 1992 to uncover concentration camps, established by

the Serbs for Muslim and Croat inmates, near the town of Prijedor in

Krajina. The carnage dragged on until soon after the Srebrenica

massacre three bloody years later.

I have kept in touch with the survivors of, and

those bereaved by, those camps, and come to understand how the

outrage of “disappearance” inflicts an immeasurable pain on those

who remain. I return to Bosnia every year for commemorations at the

camp, and hear how, in so many ways, those words “missing” and

“disappeared” are crueller than “dead”; they leave the mothers,

fathers and family without so much as an interment, a grave to

visit, an account of what happened and why.

By the time Bosnia’s war ended, in 1995, the

discipline of forensic anthropology in pursuit of the missing had

been advanced significantly: in theory by an American called Clyde

Snow, and in practice by a bold and radical group, the Argentinian

Forensic Anthropology Team, established in 1986 to trace and

identify the thousands forcibly “disappeared” during that country’s

military dictatorship from 1976 to 1983. “For the first time in the

history of human rights investigations,” wrote Snow, “we began to

use a scientific method to investigate violations. Although we

started out small, it led to a genuine revolution in how human

rights violations are investigated.” The scale of the catastrophe in

Bosnia meant that the search needed to draw on that revolution, to

which ICMP would in time add a second revolution: the introduction

of DNA matching.

When investigators from the war crimes tribunal in

the Hague first arrived in 1996 to build a case against the

perpetrators of the Srebrenica massacre, their first preposterous

task was to search for the evidence: its victims, 8,100 murdered men

and boys ploughed into the ground.

They were led by a French investigator called

Jean-Rene Ruez, an anthropologist called Richard Wright, who had

worked on World War Two graves in Ukraine, and a former

archaeologist of ancient and medieval London, Ian Hanson – who is

now deputy director of forensic sciences, anthropology and

archaeology at ICMP.

|

|

|

Remains of people massacred

during the Bosnian war are laid out on tables at the

Krajina Identification

Project in Sanski Most (Credit: Andrew Testa/Panos)

|

|

|

The modern discipline of finding and identifying

the hidden dead, Hanson says, has its roots in WWII: a famous case

was the identification of more than 20,000 Polish officers massacred

at Katyn in what is now Russia in the spring of 1940. The USSR

insisted they had been killed by the Germans, but a German

investigation disproved this, forensically demonstrating that they

had been murdered by the Russian political police, NKVD. “For once,”

concedes Hanson, “I’m afraid the Nazis were right.”

Work at Srebrenica began on what were thought to

be the five mass burial sites – each containing many separate graves

– in which the dead had been buried and left hidden. Then a macabre

truth emerged: testing showed that body parts from what became

called the primary graves had been moved to secondary ones, to hide

evidence. Sometimes, they had even been disinterred and reinterred

again, into tertiary graves. With two implications: firstly, that

more than a million-and-a-half bones and body parts from 8,100

people were scattered across innumerable sites; and secondly, that

the few byways of rural eastern Bosnia had for weeks, months, been

heaving with trucks carrying the rotting, stinking remains of these

people – some 3.2 tonnes of “putrefactive material” – hither and

thither. Yet no one said a thing.

“We call this ‘grave-robbing’,” says Hanson.

Enquiries by him and others found that the Serbs had arranged

secondary graves “to be located in places where there had been armed

confrontations, so that they could plead that massacre victims were

killed in combat. It was all very carefully worked out.”

The search for the missing was initially regarded

as a humanitarian affair. But the war crimes tribunal’s motivation

was prosecutorial. When ICMP arrived in 1996, it dovetailed into

that notion, so that its approach was altogether new, and tougher:

finding the hidden dead for human reasons, but also seeking evidence

to establish what happened and uphold the rule of law. The victims

clearly approve: of the relatives of the missing who gave blood

samples in pursuit of a DNA match, 90% agreed to allow any results

to be used in evidence at trial.

Denial and obstruction

From the outset, the process of finding and

identifying the dead was hampered by a toxic atmosphere of denial,

non-cooperation and sectarian structures that dealt with their own

side’s losses and no one else’s – markedly among the main

perpetrators responsible for more than 80% of the missing, the

Bosnian Serbs.

“When we first arrived,” says Hanson, who was then

with the war crimes tribunal, “the people with the information we

needed were not nice guys; they were guys with guns not wanting us

to do what we had come to do. We used to go into the police stations

that were supposed to be helping us, and see pictures of ourselves

on the wall: ‘Do Not Cooperate with These People’!”

To that end, ICMP stepped in, not just to help

look for bodies and nurture the expertise to do so, but to “assist”

the Bosnian government in turning a haphazard, sectarian search into

a systematised, centralised operation. Hanson uses the word 'assist'

but moves his flattened palms against thin air making as if to push

it.

The initial search focused mainly on Srebrenica.

Identification both there and in Krajina was at first done using

classical anthropological methods: identifying possessions, dental

treatment, clothing etc. But from 2000, ICMP began using DNA samples

from blood given by relatives of the dead, matching them with those

gleaned meticulously from samples of excavated bone. This was the

second revolution in forensic anthropology and the figures speak for

themselves: in 1997, seven positive identifications; in 2001, 52; in

2004, 522.

Srebrenica has become iconic of Bosnia’s carnage,

yet it tends to detract from other atrocities over the three years

of the war. Bosnia is a country without a reckoning, a call to

account. And nowhere is this more brutal than in Krajina, with the

second-biggest concentration of mass graves, the first of which was

found in 1999 at Kevljani. Near what had been the iron ore mine of

Omarska, it contained 143 bodies of men murdered in the camp.

A second grave was found at Kevljani, this one

with 456 victims of Camp Omarska, and others around a mining

facility at Ljubija. But only in 2013 did Bosnia’s largest mass

grave away from Srebrenica come to light, a few kilometres away down

a dirt track from Omarska, by which time the site of the camp had

been re-opened as a mine: the grave at Tomasica in which Fikret

Bacic found his brother. The site looks like a pond now, water

settled in the sunken earth, from which reeds grow. A family from

the nearby Serbian village walk up the track towards it, carrying

fishing rods. But for more than a year, this was a scene unlike

almost any other in Bosnia since the war.

|

|

|

The site of the mass grave at

Tomasica. So far more than 400 bodies have been

exhumed,

but authorities believe many more may be buried

there (Credit: Andrew Testa/Panos)

|

|

|

“They arrived here, all of them,” recalls Dijana

Sarzinski, mortuary manager at the Krajina Identification Project

(KIP) facility on the edge of Sanski Most. “It’s one thing to exhume

bodies from a grave of 11 people, as many of them are. But here were

434, possibly more.” The figure would later rise to nearly 600.

“They had been preserved in clay for 20 years, tightly packed

together, glued by decaying tissue.” Here was the KIP’s extreme

exposure to a science called taphonomy – that of the decomposition

of organisms, known by the initials FBAAD: fresh, bloat, active,

advanced, dry. “It’s a bit different when you see people staring at

you from the earth: their eyelashes, lips, fingerprints. You get

used to the smell of bodies, but not like they were at Tomasica. We

all had PTSD after Tomasica.”

Investigators at Tomasica found a terrible echo of

the grave-robbing that they had discovered at the other end of the

country: evidence of matching body parts in different graves. The

practice of disinterring and reinterring bodies, by now so

perturbingly familiar from work around Srebrenica, had actually

begun here three years earlier than it had there.

One of the human agonies of this separation of

body parts is that some people are identified on the basis of just a

few bones, and it is up to the families to decide whether they have

enough to bury or whether to wait for more.

“People find their missing, but not complete,”

says Amor Masovic, who set up the Muslim-Croat Federation Missing

Persons Commission after the war. “They don’t know if they have

peace or not. They may bury a few fingers and a leg, and five years

later there’s a knock at the door, it’s the left leg now, two years

later a piece of skull. It’s part of that awful limbo.” At one

point, Islamic spiritual authorities decreed it irreligious to bury

less than 40% of a body, further exacerbating the trauma for those

believers trying to deal with fragments.

“During the siege of Sarajevo,” recalls Masovic,

the Bosnian Serb general Ratko Mladic “told his gunners: ‘Drive them

to the edge of madness’. Well, this was the same principle, but for

the madness to remain after the war. The madness of relatives of the

missing, which will remain until their own deaths. They appear as

statistics, all 40,000 of them. But each number is a horror story

that people are going through, every one of them like a novel you

could read for the rest of your life.”

|

|

|

Remains of a life before the

horror (Credit: Andrew Testa/Panos)

|

|

|

The bodies from Tomasica, like those from all

around Krajina, come first to the identification facility on the

edge of Sanski Most. The standard operating practice here is the

world’s “gold standard”, says forensic anthropologist Dijana

Sarzinski. Remains are meticulously washed, and a biological profile

established. Scientists and technicians work in silence, clad in

blue tunics and masks, washing body matter, cleaning bones with

toothbrushes. The bones are subject to a physical decontamination,

followed by removal of any exogenous DNA that may have attached

itself. A small sample of bone – a “bone window” – is then extracted

with precision blades, to be passed on to the laboratories. “We’re

not allowed, as anthropologists, to determine a cause of death –

that’s for the pathologists,” says Sarzinski. “But we can prepare

the cases and point out possible causes.” The single bullet holes

through the skulls of these men from Hozica Kamen are articulate

enough.

The numbers arriving from Tomasica were so

overwhelming that the bodies “had to be treated with salt, basically

mummified, using a method thousands of years old, preferred by the

ancient Egyptians,” she says. “They had been preserved in clay for

so long, and very quickly decompose – through dessication of tissue,

bugs and maggots”.

The bodies from Hrastova Glavica, a desolate

mountain hamlet near Sanski Most, presented a different challenge.

In August 1992, the Serbs brought 125 prisoners here by bus from the

camps at Kereterm and Omarska. They took them off the buses bound in

groups of three, gave each man a cigarette, shot them and slotted

them individually down a crevice in the rocks. (The grave was found

because one man broke free and survived to tell the tale.) “Body

parts had been squashed together for so long, they were all

co-mingled, tissue stuck together, tissue and bone from one body all

mixed up with another,” Sarzinski says.

Once the bones are ready, they have to be

re-associated with others from the same skeleton; this is crucial to

establish what grave-robbing has taken place. “It became very

quickly clear that of the 434 bodies we received from Tomasica, 56

cases of body parts needed re-associating with cases which had been

previously identified at Jakorina Kosa,” says Sarzinski. But others

enter into the category of ‘NN’, no name.

ICMP started an NN Project in 2013, explains

Sarzinski, “to give names to associated skeletons that had none”.

The project is “all-encompassing”, she says. “It throws together

everything we have and can get, from the police, the families, the

prosecutor’s office, seeking out new areas of investigation and

pushing for them, trying to fit any and every tiny part in a huge

jigsaw puzzle.”

I ask whether Sarzinski would like to come to this

year’s commemoration at Omarska – put faces to the bones, as it

were. “I can’t,” she replies. “I have to do this job for what it is.

I can’t afford to cross that line.”

|

|

|

Victoria-Amina Dautovic, a

forensic scientist, trains on a synthetic skeleton

at a mortuary facility in Visoko, near Sarajevo

(Credit: Andrew Testa/Panos)

|

|

|

One of the reasons that so many of the dead in

Tomasica have been identified is that many relatives from around

Prijedor had given blood samples. ICMP’s revolutionary DNA-matching

process proceeds from Sanski Most and the other mortuaries to the

organisation’s core, in Sarajevo. The kernel of this entire

operation is the DNA lab, a small, unprepossessing room on the first

floor of a modern office block.

Ana Bilic is deputy head of ICMP’s laboratories

division. Like Sarzinski, she is young, and testimony to this

singularly strange speciality Bosnia’s tribulation has produced:

born in Sarajevo, she trained at the university here before

completing a Master’s at Halifax, Canada, and returned to do this

work. There is a logic to Bosnia becoming a world leader in this

grisly expertise, in addition to the experience of war: medical

science was practised in communist Yugoslavia to a markedly high

standard, and science now serves as some kind of absolute that

transgresses the bitter divide of war, and might even transcend it.

The Sarajevo facility is the hub of a network of laboratories in

Bosnia, Croatia and Serbia – politically balanced.

It takes three weeks for DNA-matching to take

place. On one side of the process, there are the reference samples

of blood from relatives of the dead, collected during exhaustive

drives in Bosnia and among the scattered, shattered diaspora across

Europe and America. Bilic shows me one of the so-called IsoCode

cards on which blood arrives from the relatives: six drops from the

right index finger, air-locked in a plastic bag. The blood is valid

for DNA testing for 20 years, explains Bilic. The DNA in the blood

is then bar-coded, given a digital existence that may or may not

help it find its match.

On the other side are the bone samples from places

like Sanski Most. The scoured bone windows are “ground into a fine

powder, to increase the surface available for testing,” says Bilic,

and 0.5–1g of the bone powder is, like the blood, bar-coded inside a

small plastic bag. Bilić produces one: “Some of these people have

been dead a long time, stacked up in clay, rivers and canyons, and

it’s a challenge to extract the DNA.” She shows a chart

demonstrating that some bones are easier than others – teeth,

vertebrae and talus bones (in the ankle) are best, she says, for

extraction of osteocytes, a variety of cell in which DNA is more

likely to be preserved.

The method of DNA identification preferred by

ICMP, explains Bilic, is nuclear short tandem repeat. It concerns

the number of times a nucleotide is repeated consecutively on the

DNA strand. She says that this method has a “higher discriminatory

power” than any other, “and a certainty threshold of 99.95%,

sometimes higher, often 99.999 recurring. As close to certain as it

is possible to get.”

And into the computer they go: bar codes from the

bone, and those from the blood samples – sorted by a specially

devised “blind” programme – blind, not least, to political rhetoric,

manipulation, denial. Cold, clean science to enact, says Bilic,

“blind searches of kinship analysis, so that the possible

identification of the person can be made. Without the use of DNA,

there would be no way to put these parts of the puzzle together

again.”

The system’s near-perfection produces many

matches, but also leads to a new set of problems: the discovery of

mis-identifications using earlier, less accurate methods. As Amor

Masovic explains: “About 8,000 were identified through classical

methods, of which some are completely wrong – they have two left

legs, they are part-one person, part-another.

“With DNA testing, some families realise the

person they buried 15 years ago was a mistake. They will know that

their son has been identified, but is in a mortuary in Sanski Most,

or Banja Luka, not in the ground. And this agony begins: of

disinterring the misidentified body, and replacing it with the

correct remains.” But the Muslim-Croat Federation Missing Persons

Commission has a policy, Mašovic says: “We will not disturb people

in the ground – because it only disturbs the families – unless we

have found another body to replace it. We can correct a mistake, but

we can’t take a body from a family if there is none to replace it.”

Down the corridor from Bilic’s lab, Ian Hanson’s

depth of commitment allows him no respite; he almost corrodes

himself with his own questions. “When I moved here from the ICTY

[International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, in the

Hague] in 2009, we’d found 70% of the missing. Why are we not

finding more? Why are there are still 8,000 people missing? There

are reasons for that.”

The cruellest, most effective, impediment to their

work is the rule of silence – observed when body parts were being

moved along lanes near Srebrenica and Omarska, and observed still.

“One of the constant issues we face,” says Hanson, “is that someone

knows where the graves are, but everyone gets on with their

business. People know, without giving us the information. It’s an

issue among the Serbs in Krajina, the Bosniaks in Sarajevo, the

Croats in Mostar. They’re reluctant to come forward, or scared of

intimidation.”

A series of US government cables from 2008 –

posted by Wikileaks – show how much the Serb administration,

Republika Srpska, has impeded efforts to find the missing. One says

that “authorities have taken a series of steps to undermine the

ability of the state-level Missing Persons Institute (MPI) to

locate, exhume and identity victims”. A further cable says that a

separate Serb-only missing persons agency has taken “increasingly

bold steps to undermine” the central, non-sectarian MPI. This Serb

agency is empowered to “withhold information from MPI,” the cable

says, and has even engaged in “confiscation of MPI material”.

“What is the incentive for people to help us when

the risk is so high?” asks Hanson. “They all keep quiet, not even

wanting to implicate the others, in case they implicate themselves.

But they all want an outcome. We can go into a room full of people

who do not want to work with each other – but they all know that we

are the ones who do the DNA tests that lead to bodies being found.

So the question to them all is: Do you want these people found or

not?”.

|

|

|

DNA analysis has transformed the

work here (Credit: Andrew Testa/Panos)

|

|

|

Hava Tatarevic’s garden is ablaze with the palette

of summer. Scarlet begonias, white marguerite daisies with yellow

suns at their core, deep pink climbing roses – and smoky blue

forget-me-nots, for that Mrs Tatarevic could never do, whether

before her husband and six sons were found, or after.

She is the older sister of Zijad Bacic’s murdered

mother, and she survived – “if you can call this survival,” she says

– to tell the story of the night she lost her family, some weeks

before the murder of Zijad’s. “It was one of the first days of the

war. Men came to the house, and took them all away. They took my

husband, Murharem. And six of my sons: Senad, Sead, Nihad, Zijad,

Nidzad and Zilhad. All apart from my youngest, Semir. They said he

was too young. They came to the house with guns, and balacavas, and

just said: ‘You’re coming with us, if not we’ll kill you all, here

and now.’ I started to cry, and they said: ‘Don’t worry old lady,

they’ll be back.’ And marched them down the hill.

“I never saw my sons again, but a few days after

that, the same men came back and ravaged everything. They stole what

they wanted from the house, ate and drank what was here, and smashed

the rest. They killed all our animals. They said there was a

restaurant down on the road by the viaduct, where I was supposed to

go. But they said: ‘Don’t go there, it’ll upset you. It’s full of

children hungry and crying’ – I think many of them were killed. So I

was taken instead to the camp at Trnopolje, then on the convoys to

Travnik. From there, after a long time, my sister came and took me

to Croatia, and then Germany.”

Mrs Tatarevic pauses. The only sounds audible are

bees across the flowerbeds and the hum of a tractor in mid-distance.

She offers coffee, but it seems too much trouble. “I started looking

for them all right away,” she continues after a while. “First of all

I looked around the refugee camps. I wrote letters. People would

come to Germany from all over the diaspora, and I’d ask them: have

you seen my children? Have you seen my husband? I started coming

back in summer to rebuild the house, and plant things. And I asked

everyone, even the Serbian neighbours: have you seen them? Do you

know where they are?

“I went to the police in Sanski Most to register

them. I gave my blood sample to the people from Sarajevo. I went to

Trnopolje where the concentration camp had been, and asked people

there. I don’t know how I survived the pain. I don’t know if I did

survive the pain. I just wanted to know – how did they die? Are they

still alive? Might they come back to the village while I am in

Germany? If they were dead, all I wanted to do was to hold their

bones in my hands, and find a place of green grass under which to

bury them, and say my prayers and say: there they are, my dead

sons.”

Then, after almost a quarter-century of this

purgatory, she learned about the new mass grave found in 2013. “I

think I knew, I had a sense, something told me this was it. We went

to Bosnia on the Sunday, to the grave site, to Tomasica. There was a

grave full of children and young people from our village. And there

was one of my sons, Senad, still with his wedding ring on. And I

knew, even before they took the others to the laboratory, a voice

told me it was them, the other five. And yes, later, a woman came:

‘We have your husband, we have your sons,’ she said.”

Dusk falls across the heat haze. The sound of the

evening muezzin drifts across the valley – once intended never to be

heard here again. Insects buzz across the flowerbeds as the cool of

evening descends. The brutal bedlam of those days and nights 24

years ago seems unimaginable, but Mrs Tatarevic’s gracious presence,

and falling tear, make it only too cruelly real. “It is hard enough

to lose a child, I think. But to lose them all? What can I say? What

can I do? I cannot jump out of my skin into another. I just have to

do what I can with my own. And they are buried now. The wait is

over.”

--

Additional research by Elsa Vulliamy and

Victoria-Amina Dautovic.

This article was first published by Wellcome

on Mosaic and is

republished here under a Creative Commons licence. |

|

|

|

BOSNIA |

PAGE 1/2 ::: 1 | 2 |

|

|

|

|